Lot Archive

The Important Battle of Britain fighter ace’s C.V.O., D.S.O., D.F.C. and Second Award Bar group of eleven awarded to Group Captain Peter Townsend, Royal Air Force, who in February 1940 became the first pilot to bring down an enemy aircraft on English soil, later commanding No. 85 Squadron from May 1940 until June 1941, a period that witnessed him completing over 300 operational sorties, twice taking to his parachute - once when wounded - and raising his score to at least eleven enemy aircraft destroyed.

Appointed Equerry to H.M. King George VI in 1944, and Comptroller to the Queen Mother’s Household in 1953, his famously controversial and ultimately forlorn romance with the Queen’s sister, Princess Margaret, brought him further celebrity status to add to his spectacular wartime achievements.

Turning his attention to writing, in later years he authored the classic Battle of Britain memoir ‘Duel of Eagles’ whilst his well regarded 1978 autobiography ‘Time and Chance’ tells the story of his eventful personal life.

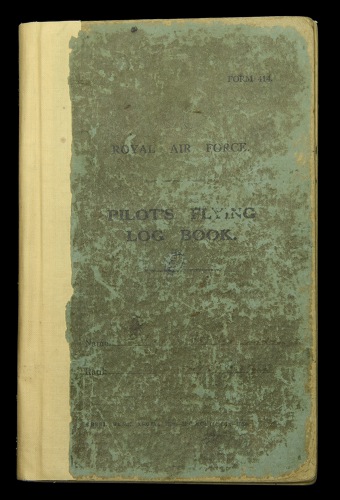

To be sold with the recipient’s original Flying Log Books, bound in one volume - with later annotation in his own hand - covering the entirety of his operational career.

The Royal Victorian Order, C.V.O., Commander’s neck badge, silver-gilt and enamels, the reverse officially numbered ‘C1106’; Distinguished Service Order, G.VI.R., silver-gilt and enamel, the reverse of the suspension bar officially dated ‘1941’; Distinguished Flying Cross, G.VI.R., with Second Award Bar, the reverses of the Cross and the Bar both officially dated ‘1940’; 1939-45 Star, 1 clasp, Battle of Britain; Air Crew Europe Star; Defence and War Medals 1939-45, with M.I.D. oak leaf; Coronation 1953, unnamed as issued; Jubilee 1977, unnamed as issued; Netherlands, Kingdom, Queen Juliana’s Coronation Medal 1948; Order of Orange-Nassau, Officer’s breast badge, silver-gilt and enamel, with rosette on riband, breast awards mounted court-style in this order, and all housed in an attractive custom made glazed leather display case, with sterling silver plaque, engraved ‘Gp. Capt. P. W. Townsend R.A.F. C.V.O. D.S.O. D.F.C.’, last with enamel damage, contact wear overall but generally good very fine unless otherwise stated (11) £160,000-£200,000

Provenance: Sotheby’s, November 1988 (when titled as “The Property of the Recipient”); Dix Noonan Webb, December 2004.

D.S.O. London Gazette 13 May 1941.

The concluding paragraphs of the original three page recommendation state: ‘Acting Wing Commander P. W. Townsend, D.F.C., has been engaged in active operations against the enemy without respite, except for the very short period when he was wounded, since the outbreak of War. He has flown over 300 operational flights including 95 at night. During the Battle of Britain he led every patrol against the enemy except one and it will be noted that the Squadron total was excellent in comparison to its losses. This very light loss of pilots by No. 85 Squadron can only be attributable to the excellent, courageous and well thought out leadership of its Commanding Officer.

No. 85 Squadron was the first Squadron in the R.A.F. to reach treble figures in conclusively destroying enemy aircraft. Though some of this number was destroyed before Acting Wing Commander Townsend took over command of No. 85 Squadron, the balance can without doubt be credited to the training, personal leadership and high devotion to duty of its Commanding Officer.

Acting Wing Commander Townsend since taking over command of No. 85 Squadron has infused into his pilots and ground personnel a spirit of tremendous keenness and devotion to duty by his example and personal character. Apart from his ability as a leader he is a gallant, determined and courageous fighter. Acting Wing Commander Townsend in all has destroyed eleven enemy aircraft, probably destroyed three, as well as damage others.’

D.F.C. London Gazette 30 April 1940.

The original recommendation states: ‘On the 8 April 1940, whilst on patrol over the sea off the north east coast of Scotland, Flight Lieutenant Townsend intercepted and attacked an enemy aircraft at dusk and after a running fight shot it down. This is the third success obtained by this pilot and in each instance he has displayed qualities of leadership, skill and determination of the highest order, with little regards for his own safety.’

D.F.C. Second Award Bar London Gazette 6 September 1940.

The original recommendation states: ‘This officer assumed command of a Squadron after its return from France at the end of May 1940, and in a very short time, under his leadership and guidance, it became a keen and efficient fighting unit. On 11 July 1940, whilst leading a section of the Squadron to protect a convoy, he intercepted about twenty or thirty enemy aircraft, destroying one and severely damaging two others. The enemy formation was forced to withdraw. Under his command, the Squadron has destroyed eight enemy aircraft while protecting convoys against sporadic enemy attacks. On 18 August 1940, his Squadron attacked some 250 enemy aircraft in the Thames estuary. He himself shot down three enemy aircraft, the Squadron as a whole destroying many others. The success which has been achieved since Squadron Leader Townsend assumed command, has been due to his unflagging zeal and leadership.’

M.I.D. London Gazette 11 July 1940.

Peter Wooldridge Townsend was born in Rangoon, Burma on 22 November 1914 and was brought home to be raised in Devon. Educated at Haileybury, he entered the R.A.F. College, Cranwell in September 1933, and graduated top of his entry, his first official posting being to No. 1 Squadron. In 1936 he transferred to No. 36 Squadron in Singapore, during which period he flew Vildebeest Torpedo Bombers - ‘a big biplane as ugly as its African namesake’ - but before the outbreak of hostilities, Townsend had returned to the U.K. and joined the “Fighting Cocks”, No. 43 Squadron. Within a very short space of time, he was to be wounded by cannon-shell, twice shot down, and awarded the D.S.O., D.F.C. and a Second Award Bar to his D.F.C. In fact, Townsend epitomised the very spirit of Churchill’s famous “Few” and rapidly became a household name.

The sort of conditions under which Townsend achieved such fame are best summed up by the Royal Air Force Museum at Hendon’s description of a typical Battle of Britain pilot: ‘In 1940 he had total control of a 350 m.p.h. fighter but, no radar, no autopilot and no electronics. His aircraft was armed with eight .303 machine-guns (the same calibre as a soldier’s rifle). His opponent had cannon. His aircraft was unarmoured yet over 90 gallons of fuel was situated in front of his lap. He had no helmet or protective clothing, save a silk parachute. He had three seconds to identify his foe and little more to pull himself clear of the cockpit if hit. He could have been only nineteen years old.’

First Pilot to Bring Down a “Raider” on English Soil

By the outbreak of war, Townsend was a Flight Commander but, like most of his contemporaries, without combat experience. In comparison to their Luftwaffe opponents, this was a serious shortcoming which would result in terrible casualties. However, the R.A.F. possessed its fair share of “natural aviators” and it was these men who rapidly asserted themselves during those bleak days of 1940. Among their ranks was Peter Townsend, who, following his very first combat, emerged with the envious accolade of having brought down the first German raider on English soil. The Heinkel III had fallen victim to his Hurricane’s guns on 3 February 1940, crash landing near Whitby in Yorkshire. Townsend visited one of the survivors in hospital and later laid a No. 43 Squadron wreath on the graves of the less fortunate crew members.

The Squadron transferred to Wick at the end of the same month and not long afterwards, while patrolling over Pentland Firth, Townsend claimed his next victim. Although he had just been instructed to return to base, Townsend adopted the “Nelson touch”, shut off his radio contact and set off in pursuit of two Heinkels which had momentarily come into view. His ensuing attack on one of them was executed with devastating effect:

‘ ... Streaming vapour from its engines, the bomber was going down, but the rear gunner, seeing me silhouetted against the after glow in the north-west, was still putting up a desperate fight. I went in again, guns blazing down his cone of tracers until as I dodged below I could hear his MG 15 machine-guns still firing just above my head. He was a brave man fighting for his life, as I was for mine; two young gladiators between whom there was no real enmity. It was a pity that one of them - and his comrades - had to die ...’ (Duel in the Dark, by Peter Townsend, refers).

Back at base, Townsend found that his Hurricane had been riddled with machine-gun fire. It was a lucky escape. Many of the pilots who had fought over France were less fortunate and it was therefore not surprising that at the age of twenty-five, Townsend became a Squadron Leader, and, on 23 May 1940, he arrived at Debden as the newly appointed C.O. of No. 85 Squadron. His predecessors had either been killed or wounded and the more junior casualties had been replaced by young men in their ’teens or twenties. By comparison, Townsend was already an “old hand”. Unfortunately, as he would later observe, experience alone was not enough; luck, too, played a big part in survival.

Battle of Britain Squadron Commanding Officer

By now the Luftwaffe was wreaking havoc among our defenceless convoys and many fierce combats were being fought over the sea. Up in the front line of convoy defence was No. 85 Squadron, and its modest and conscientious leader, Peter Townsend. On 11 July he intercepted a lone raider off Southwold:

‘ ... Townsend was a peacetime pilot, a flyer of great skill and experience. His eight Browning machine-guns raked the bomber. Inside the bomber there were ‘bits and pieces everywhere: blood-covered faces, the smell of cordite, all the windows shot up’. Of the crew, the starboard rear gunner was hit in the head and fell to the floor. A second later another member of the crew - hit in the head and throat - fell on top of him. There was blood everywhere. But ‘our good old Gustav Marie was still flying’, remembered one of the crew. Townsend had put 220 bullets into the Dornier but it got home to Cambrai, and all the crew lived to count the bullet holes ...’ (Fighter, The True Story of the Battle of Britain, by L. Deighton, refers).

Meanwhile, Peter Townsend had his own problems. The enemy rear gunner had hit his coolant system and when still 20 miles from the English coast, the engine stopped. Reluctantly, he clambered out of Hurricane P2716 and took to his parachute. He was eventually ‘fished out of the water by the good ship Finisterre, a trawler out of Hull’. Sodden but unhurt, he was landed at Harwich. After a nip of rum and a change of clothes, he was ‘back in form’ for a patrol that evening.

On 11 August, Townsend led Yellow Section of his squadron to the defence of another convoy. At 300 yards he got in several bursts on a Dornier 17 and set the right-hand engine on fire. Moments later he was attacked head on by an Me. 110 - it passed him ‘pretty close’. Then on 18 August, in a furious combat somewhere over the Thames Estuary, Townsend accounted for three enemy aircraft in a matter of minutes:

‘ ... A dozen Me. 110s cut across us and immediately formed a defensive circle. “In we go,” I called over the R./T., and a moment later a Me. 110 had banked clumsily across my bows. In its vain attempt to escape, the machine I was bent on destroying looked pathetically human. It was an easy shot - too easy. For a few more seconds we milled around with the Me. 110s. Then down came a little shower of Me. 109s. Out of the corner of my eye I saw one diving for me, pumping shells. A quick turn toward it shook it off, and it slid by below, then reared up in a wide left hand turn in front of me. It was a fatal move. My Hurricane climbed round easily inside its turn. When I fired the Me. 109 flicked over and a sudden spurt of white vapour from its belly turned into flame. Down came another. Again a steep turn and I was on its tail. He seemed to know I was there, but he did the wrong thing. He kept on turning. When I fired, bits flew off, the hood came away and then the pilot baled out. He looked incongruous, hanging there a wingless body in the midst of this duel of winged machines ...’ (Duel of Eagles, by Peter Townsend, refers).

Despite these heartening successes, the strain of commanding an operational fighter squadron was beginning to take its toll - such was the unrelenting ferocity of No. 85’s agenda that after moving to Croydon, no less than 14 of its 18 pilots were shot down, two of them twice:

‘ ... Our dispersal point, with ground crews’ and fighter pilots’ rest rooms, was in a row of villas on the airfield’s western boundary. Invariably I slept there half-clothed to be on the spot if anything happened. In the small hours of 24 August it did. The shrill scream of the deafening crash of bombs shattered my sleep. In the doorway young Worrall, a new arrival, was yelling something and waving his arms. Normally as frightened as anyone, not even bombs could move me then. I placed my pillow reverently over my head and waited for the rest. Worrall still had the energy to be frightened. I was past caring. It was a bad sign; I was more exhausted than I realised ...’ (Duel of Eagles, by Peter Townsend, refers).

Back in action on 26 August, Townsend led No. 85 in an attack against a force of 15 Dorniers and 30 Me. 109s. At length, the fighter escort was compelled to withdraw because of the range, but not before Townsend had led in a head-on attack:

‘ ... I brought the Squadron around steadily on a wide turn, moving it into echelon as we levelled out about two miles on a collision course. Ease the throttle to reduce the closing speed - which anyway only allowed a few seconds to fire. Get a bead on them right away, hold it, and never mind the streams of tracer darting overhead. Just keep on pressing the button until you think you’re going to collide - then stick hard forward. Under the shock of negative G your stomach jumps into your mouth, dust and muck fly up from the cockpit into your eyes, and your head cracks on the roof as you break away below ...’ (Duel of Eagles, by Peter Townsend, refers).

Three Dorniers failed to return to base. Two days later Winston Churchill witnessed the Squadron in action during a visit to coastal defences on the south coast. Above him, Townsend and No. 85 were busy bringing down six Me. 109s for no loss. On 29 August, he claimed yet another victim, this time a 109 which succumbed to a five second deflection burst and crashed near Hastings. And on the following day he damaged an Me. 110 over Beachy Head. During these last days of August the Battle reached unprecedented levels of ferocity and on the last day of the month 40 of our pilots were shot down. Townsend was among them but miraculously survived. The Squadron had been scrambled from Croydon just in the nick of time and as its Hurricanes cleared the perimeter fence, enemy bomb blasts temporarily cut the engine of Townsend’s aircraft. He was relieved to see the remainder of his pilots emerge safely from a ‘vast eruption of smoke and debris’.

Climbing to full boost, No. 85 caught up with an enemy fighter escort 9,000 feet over Tunbridge Wells. Unfortunately, they had run into the experts of Erprobungs Gruppe 210. As Townsend swept into the attack he was engulfed by ‘a shower of Me. 109s, spraying streams of tracer from behind’. The pace was fast. Seconds later he gave a short burst at a turning 109 and registered enough hits to slow it down. Then another, which rolled over into a dive streaming vapour. A third one was just below, the pilot clearly discernable, but while manoeuvring to shoot, an Me. 110 came at him head-on, guns blazing. Hurricane P3166 shuddered under a torrent of point blank cannon fire and broke off into an earthward dive. Inside, Townsend grappled desperately with the controls, the pain from a serious foot wound the least of his worries. With petrol showering his uniform, the prospect of being trapped in a burning cockpit must have been vividly apparent. Assuring himself that a crash landing was out of the question, he flung back the shattered canopy and clambered out at 1,400 feet. Swaying towards the Kent countryside he saw two housemaids in a garden, staring open-mouthed. In a characteristic tone he called out, “I say! Would you mind giving me a hand when I get down?” Townsend was fortunate to avoid some tall oaks and finally came to rest amongst a clump of fir saplings. Having convinced the Home Guard and a policeman of his nationality, everyone adjourned to the Royal Oak, Hawkhurst, for drinks all round. He was eventually waved off by a ‘wonderfully friendly little crowd’. That night a surgeon removed a 20mm. cannon shell from his left foot. As Townsend passed out under the anaesthetic, he could faintly hear the sirens wailing - he was in Croydon General Hospital. Meanwhile, villagers in Hawkhurst had put his parachute on display and raised £3 in as many hours for the Spitfire Fund - not much consolation for a wounded Hurricane pilot!

By 21 September Townsend was walking with the aid of a stick (but less one toe). He returned to the Squadron, and, having flown a few aerobatics in his new Hurricane - and collected sufficient witnesses - persuaded 85’s Medical Officer that he was fit to return to operations. However, for the moment at least, No. 85 had been withdrawn from the battle zone - casualties had been too great. Nonetheless, Townsend and his pilots could reflect on a magnificent fighting record: in the previous month alone, they had claimed 44 enemy aircraft destroyed, 15 probably destroyed and at least 15 more seriously damaged. Townsend was awarded his second D.F.C.

The Blitz

In October 1940, Townsend received a signal from Fighter Command H.Q.: ‘No. 85 Squadron has been selected to specialise in night fighting forthwith’. The Blitz was now in full swing and the authorities were anxious to find a solution to the almost unopposed Luftwaffe night offensive. Hurricanes were hardly suited to this new role but Townsend was hopeful of Air Ministry support, and with the necessary backing and training results might be achieved.

Night in and night out the Squadron spent many gruelling hours groping around the darkened skies of England. It was a trying and dangerous time, and, in the main, unrewarding. There were numerous fatalities from bad weather and emergency landings on blacked-out alien airfields, Townsend nearly joining them after a nasty “prang” in fog during November. Then there were the enemy fighters who strafed their airfield by day and night - Townsend once being pushed to safety by a junior officer.

At length, the Squadron was moved to Gravesend and the very heart of the Luftwaffe’s night offensive, and in early 1941 it moved to Debden, north of London. Days after their arrival, the aerodrome was visited by the King and Queen. Douglas Bader and No. 242 Squadron dropped in for the occasion, but as Townsend would later recall, even royal visits could be rather nerve-racking:

‘ ... The officers and men of our two squadrons were ranged stiffly inside a hangar. Just before the arrival of their majesties, Douglas (whom I had first met during the day fighting) confided in me, “Look, old boy (his standard opening gambit), the one thing I can’t do is stand properly to attention. So if I overbalance, please come to the rescue.” As the royal inspection proceeded I waited nervously for Douglas, tin legs and all, to crash to the ground. Luckily, by parting his feet slightly, he remained upright ...’ (Duel in the Dark, by Peter Townsend, refers).

By the new year Townsend was beginning to get some response for the equipment required to carry out the night fighter role. Nonetheless, it was painfully apparent that the Hurricane would never make a good night fighter. One consolation was the arrival of some De Wilde explosive ammunition and it was probably as a result of this delivery that Townsend gained the Squadron’s first - and last - night victory in Hurricanes, on 25 February 1941:

‘ ... The rest happened quickly. Coming in from their left and slightly above, and still concealed from the searchlights, I held on until the last moment, then pressed the firing button. A short burst - thirty rounds - and it was over. The effect of the De Wilde was terrible; the Dornier’s controls were hit, its incendiaries set on fire. Still held fast by the searchlights, the span of the wing-tips marked by its red and green navigation lights, it spiralled steeply earthward, streaming smoke and sparks, the air gunner adding to the fireworks as he poured tracers wildly into the dark. Then the stricken aircraft reared up steeply, followed by the tenacious searchlights, until as it seemed to be poised motionless at the apex of their beams, there streamed from it three parachutes. I waited for the fourth, but Paul Schmidt’s parachute got entangled in the tail-plane and got torn to shreds. Down went the Dornier again in a steep spiral, to crash with its load of bombs and its navigation lights still burning, near Sudbury in Suffolk ... ’ (Duel in the Dark, by Peter Townsend, refers).

From Hurricanes the Squadron was temporarily re-equipped with Defiants and then finally with the American Douglas DB7, or “Havocs”. So far as Townsend was concerned, the Beaufighter was probably the best aircraft to cope with night fighting, but in April, even with Havocs, everything seemed to come together at once. In fact, on 9 April 1941, the Squadron fought three successful engagements, and Townsend was involved in one of them:

‘ ... I stuck to the enemy’s tail, but during my violent evasive action to dodge his flying bullets, Bailey was floored and George unseated. However, he managed to grab the Vickers gun and pump a few bullets into the Junkers belly as we finally slid below. George - and I can still detect his chuckle - then shouted: “The bloody gun’s jammed!” I now gathered myself for another front-gun attack, and this time approached unobserved to within close range. When I opened fire we all saw a mass of De Wilde strikes and a fair-size explosion in the right engine. Then our stubborn enemy, lurching clumsily to the right, went down in a long, steep dive until he disappeared from both visual and radar contact. We had been trying to kill each other for the last half an hour ...’ (Duel in the Dark, by Peter Townsend, refers).

Townsend and the intrepid George again made contact the following evening, and, after opening fire, the former saw tracer coming from the Junkers, ‘which swung violently to the left and went down in a steep dive, streaming little jets of flames, like red and yellow silk handkerchiefs, until it was lost to my visual and George’s radar view’. One Ju. 88 damaged.

Townsend, who had now completed some 300 operational sorties since the outbreak of the War, was rapidly becoming aware that his physical and nervous resources were running low. Then in mid-April 1941 a signal arrived from the A.O.C. No. 11 Group, Leigh-Mallory, informing him that be was to be “grounded” and sent to Headquarters. Townsend requested a stay of execution and the Air Marshal responded with an extension until June. He also advised him to take things more easily and for once Townsend listened:

‘ ... That half-hour long, inconclusive combat with the Junkers 88 in early April was to me a disturbing sign ... When Leigh-Mallory granted me another two months with the Squadron, I knew I was dead-beat ... when shot down for the second time at the end of August 1940 I was already nearing the end of my tether. Otherwise I should never have rushed headlong into that swarm of Messerschmitts ... Time after time my aircraft had been hit; bullets had holed the wings and fuselage, they had zipped through the propeller past my head, between my legs even. One had exploded in the cockpit, bringing me down in the sea, yet unhurt; another had hit me, downing me once more ... The trouble was that hair-raising experiences accumulated to form stress, a word we ourselves only knew in its aerodynamic context, as applied to our beloved aircraft ...’ (Duel in the Dark, by Peter Townsend, refers).

Luckily, the Squadron’s Medical Officer knew better and Townsend’s combat days were limited. Pride and barbiturates were not enough, although with marked courage and determination, he took his turn in night patrols right up until the end of his time with No. 85, and was subsequently awarded a richly deserved D.S.O. In June 1942 he assumed command of No. 605 Squadron, recently back from the Far East, and later R.A.F. West Malling and the Free French Training Wing. But he never again flew operationally and, in 1944, was appointed to the Royal Household - a position that would ultimately lead to a clandestine and ultimately forlorn affair with the Queen’s only sibling, Princess Margaret.

Royal Romance

Initially given a three month appointment as Air Equerry to King George VI, Townsend’s charm and easy manner soon led to a permanent position being created and his duties as royal courtier extended to accompanying the Royal Family on trips, including many holidays. This inevitably also led him to become well acquainted with the princesses. He was a noticeable part of Princess Margaret’s entourage in Belfast in October 1947 when she launched the ocean liner Edinburgh Castle and he was again present beside the 18-year-old princess when she represented her father in September 1948 at the investiture of Queen Juliana of the Netherlands. ‘Without realising it, I was being carried a little further from home, a little nearer to the Princess,’ he later wrote in his memoir, Time and Chance.

In August 1950, Townsend was made assistant Master of the Household, a role that put him at the heart of the Royal Family’s administration and regularly at the King’s side. It also made him more aware than most of the seriousness of the King’s health problems. The King’s death at Sandringham on 6 February 1952, however, came as a huge shock to his daughters. Townsend, newly appointed Comptroller to the Queen Mother’s household and promoted to Group Captain on 1 January 1953, was on hand to console Margaret, observing ‘the King’s death had left a greater void than ever in Princess Margaret’s life’.

Townsend had his own void to fill also. Two years earlier his wife, most likely out of loneliness, had embarked on an affair and Townsend, the injured party, was granted a divorce. In these circumstances then, the equerry fell for the dazzling party girl princess, later describing her as ‘a girl of unusual, intense beauty … [with] large purple-blue eyes, generous, sensitive lips and a complexion as smooth as a peach.’

He was soon to discover that his feelings were not unrequited: ‘It was then [February 1953] that we made the mutual discovery [alone in a drawing room at Sandringham] of how much we meant to each other. She listened, without uttering a word, as I told her, very quietly, of my feelings. Then she simply said ‘That is how I feel, too.’ It was, to us, an immensely gladdening disclosure, but one which sorely troubled us…’

Effusing in a romantic vein he continues: ‘Our love, for such it was, took no heed of wealth and rank and all the other worldly conventional barriers which separated us. We hardly noticed them; all we saw was one another, man and woman, and what we saw pleased us.’

Whilst remaining acutely conscious of society’s constraints: ‘Marriage ... seemed the least likely solution; and anyway, at the prospect of my becoming a member of the Royal Family, the imagination boggled, most of all my own. Neither the Princess nor I had the faintest idea how it might be possible to share our lives.’ (Time and Chance: An Autobiography by Peter Townsend refers).

News of the romance spilled onto newspaper headlines following Queen Elizabeth’s Coronation in June 1953 when Margaret was witnessed removing a speck of lint from Townsend’s RAF uniform in an unmistakably affectionate and intimate gesture.

Although Townsend was extremely popular within royal circles and Queen Elizabeth was said to be sympathetic to her sister’s wishes, the couple were not fated to marry. Townsend’s position as a commoner was unhelpful but it was his status as a divorcee that was the insurmountable obstacle in 1950s Britain - The People newspaper captiously insisting: ‘It is quite unthinkable that a Royal Princess, third in line of succession to the throne, should even contemplate a marriage with a man who has been through the divorce courts.’

On 31 October 1955, Princess Margaret issued a statement ending the relationship: ‘I have been aware that, subject to my renouncing my rights of succession, it might have been possible for me to contract a civil marriage. But, mindful of the Church's teachings that Christian marriage is indissoluble, and conscious of my duty to the Commonwealth, I have resolved to put these considerations before others.’

Writer and Broadcaster

Following his time as an Equerry to King George VI and Queen Elizabeth II, and once as an Assistant Master of the Royal Household, services that witnessed his appointment to C.V.O., in addition to the Orders of the Dannebrog and Orange-Nassau, Townsend was appointed an Air Attaché in Brussels. In late 1956, however, he retired from the R.A.F. as a Group Captain to commence a new career as a travel writer and broadcaster.

In later years Townsend was drawn to the plight of some of the world’s young, not least those who were the victims of war, and, having been approached by the sponsors of the United Nations’ “Year of the Child” Appeal in 1979, travelled the world to meet such children in person. The result of his endeavours was a book about a girl who belonged to the “Boat People”, a girl who was the sole survivor of a shipwreck on a deserted reef, and he followed up this title in 1984 with a book relating the story of a boy who had been maimed by the atom bomb attack on Nagasaki. Indeed it was as a result of such stories that Townsend decided to sell his Honours and Awards at auction in London in November 1988, having found them ‘lying around in a bag at the bottom of a drawer ... I thought it would be sensible to put them to use’. And so he did, the entire proceeds being donated to a charitable fund set up to assist children.

Group Captain Peter Woolridge Townsend died on 19 June 1995.

Sold with Townsend’s two original Flying Log Books, bound in one volume with spine professionally restored and housed in quarter leather bound protective case, spine embossed in gold letters ‘R.A.F. Pilot’s Log Book Townsend’, covering the periods September 1933 to September 1937, and October 1937 to December 1943, shortly after which point he joined the Royal Household as an Equerry to the King, both with later annotation in his own hand.

Share This Page